Spectral music gets described in a lot of shorthand ways. A movement. A French school. A computer-driven style. Each label points at something real, but none of them fully explains why spectral thinking keeps resurfacing across decades, technologies, and scenes.

A more useful way in comes from how composers treat sound itself. Frequency content, internal motion, and perceptual behavior stop being background details and start driving structure, harmony, and form.

In spectral music, the spectrum behaves like a score, and musical form becomes a story about how spectra change over time.

The arc from Ligeti to laptop noise makes sense once you follow that idea instead of chasing labels. Long before spectralism hardened into named techniques in 1970s France, composers were already asking what happens when timbre leads, and notes follow.

Later, analysis tools and digital systems pushed that thinking further, until glitches, feedback, and compression artifacts felt like legitimate musical material. The materials changed. The attitude toward sound stayed recognizable.

Table of Contents

ToggleWhat “Spectral” Actually Means in Practice

A sound spectrum describes how energy spreads across frequencies. For pitched sounds, that usually means a fundamental plus partials that may line up as clean integer multiples or drift into inharmonic territory.

Bells, metal plates, and many percussive sounds rarely behave politely. Spectral composition treats that distribution as a source for pitch, orchestration, and form.

Two basic facts help explain why spectral music feels physical rather than abstract. Human hearing responds roughly from 20 Hz to 20 kHz, although the upper edge drops with age.

Loudness perception also spans an enormous range, with a commonly cited pain threshold around 130 dB SPL, and sensitivity varies strongly by frequency, with speech-relevant bands standing out as perceptually privileged.

Spectral thinking leans into that reality. Timbre stops being a decoration layered on harmony. Timbre generates harmony. Form grows out of how spectra evolve, fuse, roughen, or collapse. Scholarly overviews of spectralism often describe that shift as a paradigm change, not a new sound palette.

Ligeti as a Precursor, Timbre First, Notes Second

Ligeti did not write spectral music in the strict French sense that solidified in the 1970s. His importance lies elsewhere. He treated timbre and texture as primary structure well before spectral analysis became a common compositional tool.

Sound Mass and Timbral Focus

Analyses of Ligeti’s early 1960s works, including Atmosphères, highlight how blocks of sound replace melody and harmonic progression as the main perceptual anchors.

Dense textures saturate the surface with micro-events, so listeners stop tracking lines and start tracking color, register, and density. At that point, audible structure lives inside sound itself rather than in thematic development.

That move already points toward spectral thinking. Musical meaning comes from internal makeup and change, not from symbolic note relationships.

Micropolyphony as Perceptual Engineering

Micropolyphony often gets explained as a technical trick, with many voices moving in tight canons. On the page, it looks contrapuntal. In the ear, it behaves as timbre. Individual lines blur into a fused mass with internal motion. Ligeti later refined the approach, thinning textures so shapes occasionally surface before dissolving again.

The key idea lies in perception. What matters is how sound registers, not how it satisfies a rule system. Later spectral composers frame their goals in similar terms.

Ligeti and Spectralism, Real but Indirect Ties

Scholarly writing on Ligeti’s relationship to spectralism talks about distant resonances rather than direct lineage.

Ligeti knew spectral techniques and engaged with composers associated with the movement, but his role stays preparatory. He helped normalize the idea that sound itself could carry form.

Grisey, Murail, Dufourt, IRCAM

Spectral music becomes a recognizable historical movement in early 1970s France. Gérard Grisey and Tristan Murail sit at the center, alongside Ensemble l’Itinéraire and the research culture surrounding IRCAM.

Historical accounts often rely on Julian Anderson’s writing because it outlines how spectralism solidified as both an aesthetic stance and a practical toolbox, while also noting discomfort with the label among composers.

Hugues Dufourt introduced the term musique spectrale in print in the late 1970s. Naming matters. A name stabilizes a practice, makes it teachable, and invites critique. Once spectralism had a name, it could spread.

Grisey’s Partiels and Instrumental Resynthesis

If one piece shows up repeatedly in explanations of early spectral technique, it is Grisey’s Partiels from Les Espaces Acoustiques. Analytical sources describe its opening as derived from a spectral analysis of a low trombone E, then orchestrated by assigning instruments to individual partials.

What matters musically is not the diagram. A spectrum changes over time. Attacks bloom. Partials rise and fall. Noise components flicker at the onset. Spectral orchestration often models that temporal behavior rather than freezing a chord.

Listening to Partiels, the takeaway feels simple. The opening sonority does not function as a harmonic progression. It behaves as a snapshot of a sound’s internal anatomy, stretched across an ensemble. That is why early writers used the metaphor of instrumental additive synthesis.

Core Spectral Techniques You Can Actually Hear

Technique-focused writing helps strip away mystique. Spectral ideas translate into recognizable operations.

Common Techniques in Plain Language

- Spectral-derived harmony : Pitch collections come from partials of a chosen sound, often leading to microtonal or stretched interval grids.

- Instrumental resynthesis : Instruments take on roles as partials, noise bands, or envelope fragments, behaving together like a single compound sound.

- Fusion and distortion control : Components close to a spectrum blend into one perceptual object. Foreign components create roughness and separation.

- Morphing and interpolation : One spectrum gradually transforms into another, with continuous change acting as a formal principle.

- Perception-led form : Form tracks what listeners notice, brightness, density, roughness, register, rather than abstract counts.

High-level handbooks on spectralism emphasize that focus on perception as a defining feature.

Classical Spectral and Laptop-Era Analogs

| Spectral idea | Concert-music example | Laptop or noise-era analog | What you hear |

| Structure from spectra | Orchestrated partials from an analyzed instrument tone | Material built from FFT bins or spectral features | Harmony feels like timbre anatomy |

| Time evolution as form | Slow color and brightness shifts | Glitch processes unfolding over time | Form reads as texture change |

| Fusion and roughness | Blended or detuned partials | Distortion, aliasing, clipping artifacts | Buzzing, grit, edges |

| Tool-shaped aesthetics | Sonograms guiding orchestration | Software workflows shaping sound | Technique stays audible |

The Technology Layer That Made Analysis Normal

Spectral music is not computer music by definition. Analysis tools simply made spectral thinking easier to apply.

STFT in One Paragraph

Many spectral workflows rely on the short-time Fourier transform. Audio gets sliced into overlapping frames. Each frame becomes a frequency representation. Overlap allows smoother tracking of change.

Even mainstream signal-processing references describe 50% overlap as a common baseline, balancing time resolution and spectral stability.

Sample rate matters because it limits the highest representable frequency. Common rates like 44.1 kHz follow from sampling theory requirements that the rate exceed twice the highest frequency of interest.

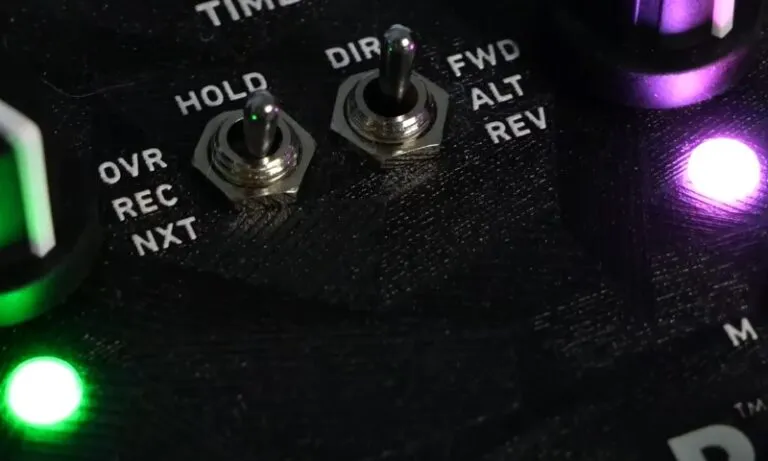

Tools That Shaped Practice

Research environments at IRCAM helped normalize sonograms as compositional tools. AudioSculpt became widely cited for spectral visualization and transformation. Max and related environments brought FFT-based processing into real-time performance contexts.

Open tools such as Partiels reflect ongoing research interest in analysis and resynthesis workflows. Sonic Visualiser and Vamp plugins made inspection and feature extraction accessible outside specialized labs.

Post-Spectral Thinking and Diffusion

By the 1990s and 2000s, spectral ideas spread well beyond a single movement. Scholarship on melody in spectral and post-spectral music shows how composers moved past stereotypes of slow timbral drift.

Debates followed. Some writers framed spectralism as an appeal to nature or psychoacoustics. Others pushed back, arguing for more careful language. At that point, spectral started behaving less like a school and more like a way of hearing.

Laptop Noise and Post-Digital Culture

Laptop-based experimental music covers a wide range, from academic computer music to harsh noise. The spectral connection does not depend on genre. It depends on attitude toward sound material.

Cascone and the Aesthetics of Failure

Kim Cascone’s writing on post-digital aesthetics argues that once digital tools stopped feeling novel, their failures became audible material. Bugs, glitches, and artifacts moved to the foreground. Many digital failures are spectral events.

Aliasing adds non-harmonic components. Clipping generates high-frequency energy. Compression smears transient spectra. Packet loss creates bursts of broadband noise.

Laptop Performance as Practice

Writing on a laptop music often frames performance as an interface and design problem. The visibility of computation, or its deliberate concealment, becomes part of the aesthetic.

Academic work on typical laptop performance practice treats tool choice as form-shaping, aligning closely with post-digital thinking.

Noise as Culture

Noise functions as a sound category and a social practice. Studies of noise scenes connect live performance, recording circulation, and technology to the persistence of noise as a genre identity. Spectral thinking shows up bluntly here. Broadband spectra, feedback peaks, and resonant bands sit at the center of the sound.

How to Listen for Spectral Thinking Across Contexts

No theory is needed here.

Listen for Color-Based Harmony

Ask simple questions. Does harmony register as brightness and density rather than chord function? Do pitch materials feel tied to resonant sources? Do slow shifts suggest a sound turning under close inspection? Those cues match how spectral scholarship frames timbre as grammar.

Track Attacks

Spectral composition treats attacks as information-rich. Transient noise and unstable partials drive the narrative. Analyses of Partiels emphasize attack modeling. In glitch contexts, attacks may appear as clicks, dropouts, or buffer ruptures, with the same focus applied to different material.

Notice Fusion and Separation

Spectral orchestration often aims to fuse components into one object or make them rub apart. Historical accounts describe that as an audible strategy.

Noise contexts handle fusion as walls of sound and separation as exposed resonant peaks or filtered bands moving independently.

A Practical Toolkit for Spectral Work Now

Institutional access is no longer required.

Analysis and Visualization

- Sonic Visualiser for spectrogram inspection and annotation.

- Vamp plugins for extracting descriptors and bridging listening with structure.

Composition and Processing

- Max and related environments for real-time FFT workflows.

- IRCAM tool ecosystems for analysis-driven transformation.

- Open research tools such as Partiels for contemporary resynthesis workflows.

Reading that Clarifies

Fineberg for definitions and techniques. Anderson for history and debates. Handbook treatments for paradigm framing. Cascone for post-digital logic. Novak for noise as culture and circulation.

Closing Thoughts

Spectral music does not live inside a single movement or technology. It lives in an approach to sound. Ligeti helped make timbre structural. French spectralists formalized analysis-driven methods.

Laptop and noise artists exposed the spectral consequences of digital systems. Across all of it, the spectrum stays central. Sound explains itself, if you listen closely enough.

Related Posts:

- Are Mini Amps Worth It? Pros and Cons Explained

- From Work to Play - The Role of Music in Every…

- 15 Times Music Celebrities Were Caught at the Casino

- Top 10 Music Streaming Platforms Every Young Artist…

- 10 Biggest Music Lawsuits in History - How Artists…

- 10 Top Tracks in C Minor - A Journey Through Music's…