Feedback is the simplest musical machine you can build. Route an output back into an input, set the gain, and listen. At first, the result can feel crude or even dangerous.

Then something clicks. The sound begins to remember itself. It reacts. It pushes back. Suddenly composition stops being about placing notes and starts becoming about shaping behavior.

Composers keep returning to feedback for a clear reason. Small decisions turn into outsized consequences. Move the microphone a few millimeters. Raise feedback by 1%. Change a delay time by a hair. The entire piece tilts in another direction.

For anyone drawn to designing conditions rather than prescribing outcomes, feedback becomes a serious compositional partner.

Today, we will have a look at feedback loops as composition tools. The focus stays on how they behave, why they feel alive, and how composers push them right up to the edge without losing control. Let’s begin.

Table of Contents

ToggleWhat a Feedback Loop Means in Musical Terms

A feedback loop exists when a signal is routed back to an earlier point in its own chain, so the present sound contains part of its past.

Every feedback system rests on three ingredients.

- A path : Air and room acoustics, cables, DAW routing, transducers, or code.

- A return amount : Gain, feedback coefficient, send level, or amplification.

- A time structure : Instant return, delayed return, or frequency-dependent phase shift.

Once the loop closes, two things happen immediately.

- The system gains memory. What you hear now carries information from a moment ago.

- Control becomes indirect. Instead of playing a sound, you start steering a system.

Engineers describe feedback using stability language for good reason. Feedback turns an amplifier into an oscillator.

Classical control theory frames the same split composers hear every day. A disturbance can decay away, or it can sustain and keep going. That line matters musically.

Why Feedback Feels Alive

Feedback does not behave randomly. It behaves deterministically while remaining sensitive.

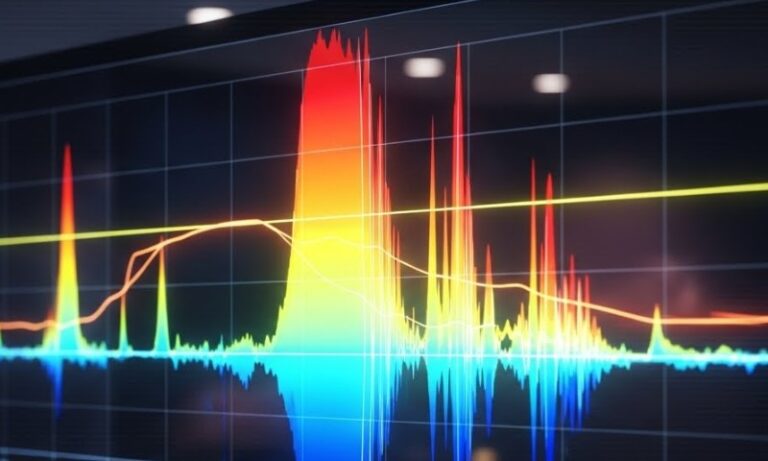

Small changes matter because the loop multiplies them over time. Adjust the loop gain slightly, and the system shifts between three broad behaviors.

- Stable decay : Echoes shrink. Energy dissipates.

- Sustained resonance : A tone locks in. Self-oscillation appears.

- Unstable growth : Clipping, saturation, or chaotic behavior takes over.

Digital delay feedback shows the same rule in plain terms. When the feedback coefficient stays below 1, echoes decay toward zero.

At 1 or higher, the system grows until clipping and distortion occur. Many composers aim for the narrow region just below that boundary, often called the edge, where the loop almost runs away but remains steerable.

At that point, the system feels responsive in a way static instruments rarely do. Gesture and reaction blur together. The sound seems to make decisions of its own.

Three Feedback Domains Composers Use

This section breaks feedback down into three practical domains composers return to again and again. Each one behaves differently, offers its own control points, and shapes musical form in distinct ways.

Acoustic Feedback – Microphone, Speaker, Room, Body

Acoustic feedback appears when a microphone picks up a loudspeaker reproducing its own signal. The room becomes part of the circuit. Room resonances decide which frequencies reinforce first. Microphone placement controls how quickly the loop finds them.

A classic example comes from Steve Reich and his work Pendulum Music. Microphones hang from cables and swing over loudspeakers. Each mic passes through a hot position near its speaker, producing bursts of feedback.

As pendulums drift out of sync, pulses phase against each other and eventually settle into continuous tones.

The score does not specify pitches. It specifies conditions. Amplifiers are set right at the threshold where feedback occurs in a target zone. Microphones are released together. The system does the rest.

What Composers Can Steal

- Treat the loop as the score, not the notes.

- Use physical motion to modulate coupling.

- Treat the end state, such as continuous tone, as structural rather than accidental.

Control Levers That Matter

- Distance and angle between the microphone and the speaker

- Gain staging

- Narrow EQ notches to tame peaks

- Speaker directionality and room placement

Environmental Feedback

Environmental feedback appears when sound is repeatedly played into a space and rerecorded, letting the room’s resonant profile take over.

Alvin Lucier demonstrated the idea clearly in I Am Sitting in a Room. A recorded voice plays back into the same room and is rerecorded again and again. Over iterations, frequencies reinforced by the room accumulate. Speech dissolves. The room’s ringing character dominates.

The piece unfolds slowly, revealing the space as an instrument with its own spectral fingerprint.

What Composers Can Steal

- Treat iteration count as form. Sections can equal the number of passes.

- Let the room compose spectral motion.

- Choose text and pacing that trigger strong resonances early.

Control Levers That Matter

- Room geometry and absorption

- Speaker and microphone positions

- Microphone pattern, such as omni or cardioid

- Capture chain noise floor, since noise becomes part of the loop

Electronic and Computational Feedback: Delays, Filters, Networks

In electronic music, feedback often means recirculating delay and filter networks. The loop might be a single delay line or a large feedback delay network used in reverbs.

Feedback Comb Filters

A feedback comb filter can be described simply. The output equals the input plus a delayed and scaled copy of the output. Signal processing texts treat it as a basic recursive filter and a model of exponentially decaying echoes.

The musical behavior follows predictable rules.

- Delay time sets the spacing of resonant peaks.

- Feedback amount sets decay time and resonance sharpness.

- Near instability, tiny changes create huge spectral shifts.

Feedback Delay Networks

Feedback delay networks, often abbreviated as FDNs, form the backbone of many artificial reverbs. Multiple delay lines feed back through a matrix, creating dense, evolving spaces.

Compositional payoff comes from treating space as playable.

What Composers Can Steal

- Build pieces around slowly changing feedback matrices.

- Modulate sparingly, since recursion compounds quickly.

- Treat reverb decay and color as form drivers, not decoration.

Feedback as a Composition Method

Feedback rewards rule writing.

Rather than saying “play E for 10 seconds,” feedback pieces often specify:

- Initial conditions such as gain, routing, or placement

- A narrow set of allowed interventions

- Stop conditions such as stabilization, saturation, or a fixed iteration count

Control theory frames stability as a property of loop gain and phase. The math helps, though it is not required. The mindset matters more. Push toward instability deliberately. Build guard rails so return remains possible.

A Practical Control Framework

A practical framework keeps feedback from turning into guesswork. By defining structure, limits, and intent up front, the composer stays in dialogue with the system rather than fighting it.

Step 1: Define Loop Topology

- Acoustic loop using a microphone and a speaker

- Recirculating delay loop

- Network loop using multiple nodes or resonant objects

Step 2: Decide What Control Means

- Stability through steady tone or texture

- Threshold behavior through pulses and bursts

- Runaway behavior through saturation or collapse

Step 3: Write Intervention Rules

- Change only one parameter at a time

- Intervene only every 30 seconds

- Move microphones without touching the gain

- Shape EQ without touching the feedback amount

Rules reduce panic and sharpen listening.

Feedback Is Easier Than Ever, and Easier to Ruin

Modern tools embed feedback as a normal parameter. Risky routing is no longer required.

In Ableton Live, delay devices describe feedback plainly. The Feedback parameter sets how much output feeds back into the delay inputs. Some instruments allow oscillators to modulate themselves through feedback, creating complex waveforms as the amount rises.

For composition, the implication stays clear.

- Feedback becomes a first-class modulation target.

- Automation curves for feedback, filter cutoff, or delay time can be scored.

- Instability zones become musical material.

A Safety Note You Cannot Ignore

Acoustic feedback and high delay feedback can become dangerously loud in seconds.

Occupational guidelines help frame risk.

- NIOSH recommends 85 dBA over an 8-hour average.

- OSHA allows 90 dBA for an 8-hour day using a 5 dBA exchange rate.

- Over a 40 year exposure, excess risk estimates reach 8% at 85 dBA and 25% at 90 dBA.

For composition practice, the takeaway remains simple. Treat feedback like power tools. Monitor quietly. Limit exposure time. Use limiters cautiously. Luck does not count as a safety strategy.

Pushing the Boundaries of Control

Pushing feedback systems to their limits reveals where sound stops behaving like a tool and starts acting like a responsive system.

In this zone, control becomes less about precision and more about guiding unstable forces without letting them take over.

Controlled Instability

The most interesting feedback pieces often sit barely on the stable side.

- The system sustains without exploding.

- Small gestures produce large changes.

- The sound reacts in ways that feel intentional.

Composers often hover just below the instability boundary, then briefly tip the system over for form, before pulling it back.

Material Specific Feedback

David Tudor pushed feedback into physical ecology with the Rainforest works. Sound vibrated into everyday objects, acting as resonant loudspeakers. Each object responded differently. Audiences walked among them.

Every installation differed. That variability was part of the composition.

What Composers Can Steal

- Use many small resonant nodes rather than one big loop.

- Accept that each setup produces a different piece.

- Compose relationships and constraints rather than identical outcomes.

No Input Mixing

No input mixing routes a mixer’s outputs back into its own inputs, turning the console into a self-generating instrument. Research on Toshimaru Nakamura frames the practice as treating the mixing board itself as the sound source.

Tiny gestures matter because the system stays near thresholds.

Practical Composition Angle

- Score allowed control moves such as mute toggles or EQ sweeps.

- Define safe states and risk states.

- Treat the performer as a regulator, not a generator.

A Composer’s Toolkit

| Feedback structure | Typical sonic result | Primary control levers | Common failure mode |

| Mic to speaker loop | Whistles, pulses, room locked tones | Placement, gain, EQ notch | Sudden SPL spikes |

| Recirculating delay | Repeating echoes, pitched ringing | Delay time, feedback amount | Runaway buildup |

| FDN reverb network | Dense evolving space | Matrix, delay lengths | Color buildup |

| Iterative room recording | Speech dissolving into drones | Iteration count, placement | Noise accumulation |

| Resonant object ecosystem | Heterogeneous textures | Transducer coupling | Dead nodes |

| No input mixer | Squeals, crackle, bursts | Gain staging, routing | Rapid runaway |

Composition Strategies That Work

Practical feedback writing lives or dies on structure. Clear strategies keep systems playable, repeatable, and expressive, even when the sound itself stays unpredictable.

Score Boundaries, Not Sounds

Define:

- Target region, such as barely stable or intermittent

- Allowed interventions

- Stop condition

The system generates content within those bounds.

Give the Loop a Body

Slow variables help.

- Pendulum motion

- Walking through a space

- Rotating speakers

- Moving transducers on objects

Slow change reduces constant tweaking and clarifies form.

Add Damping as a Voice

Damping shapes hierarchy.

-

- Band-pass filters in the loop

- Low-pass damping for decay

- Selective notches to favor certain resonances

Use Time Delay to Create Pitch

Short delays create pitched resonance. Feedback extracts tone from noise purely through time structure.

Document the System

Feedback rewards documentation.

- Routing diagrams

- Parameter ranges

- Room layout

- Notes on failures and recoveries

That discipline allows risk without repetition.

Closing Thoughts

Feedback changes how composition feels. Control becomes indirect. Sound becomes a partner rather than a servant. The composer designs conditions and listens closely as the system responds.

Pushing the boundaries of control does not mean abandoning it. It means redefining where control lives, inside the loop, shaped by restraint, patience, and curiosity.